Tripwires, heuristics and satisficing can all streamline your decision-making processes at work, if you know how to use them to your advantage.

Google ‘How many decisions does the average adult make each day’? (or allow us to do it for you) and you might be surprised by the result. Article after article quote 35,000 decisions as the standard. Cornell University research suggests 226.7 of those decisions are solely based around food (this checks out for me).

This 35,000 figure would factor in sleeping time and equate to roughly 1500 decisions per hour, which sounds excessive, says Associate Professor Guillermo Campitelli, Psychology Lead at Murdoch University.

This statistic is most likely factoring in automatic decision-making, he says, like moving our legs as we’re walking or scratching our head, so perhaps it’s not indicative of the average human’s daily mental load.

However, there is no denying that we face a mountain of decisions in our professional and personal lives every day. So learning how to strengthen our decision-making capabilities can only be a good thing. Here are some research-backed ways to do that.

Use tripwires to streamline decision-making

You may have heard the story of Van Halen’s David Lee Roth requesting a bowl of M&Ms to be backstage ahead of each performance, with all the brown M&Ms removed. If they weren’t removed, he’d flip out.

On paper, this looks like a diva meltdown 101, but what Roth was actually doing was setting up a tripwire – that is, an indicator that pulls you out of auto-pilot mode or determines the next action that you’ll take, i.e. ‘If we can’t make X happen, we need to proceed to do Y, but Y will only be deemed a viable option if Z has occurred.’

In Roth’s case, it wasn’t a hatred of brown M&Ms that enraged him, it was the indication that the people responsible for setting up the stage hadn’t paid close attention to his set-up list – which included lots of important safety information for their complex set. If they’d forgotten the M&Ms, what else had been skipped?

He didn’t waste time going around ensuring every screw was tightly wound. He just decided that he needed a tripwire that would determine if they’d proceed with the set-up or pull everything down and start from scratch.

Including your own tripwire in the decision-making process – such as ‘We will only allocate more budget to this product if it shows more than a 5 per cent ROI – helps to ease the burden of making a tough call come crunch time.

Look for satisficers

Campitelli’s research focus on decision-making was inspired by Herbert Simon, who won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1978 for his contributions to modern business economics and administrative research.

“He coined the term bounded rationality… He said decision-making models in mainstream economics [usually] assume that humans are rational, so they had to investigate if that was true.

“He decided to study chess players,” says Campitelli. “As they were playing, he asked them to say out loud what they were thinking. He looked at patterns of how they make decisions, and [off the back of this], he coined a term called ‘satisficing‘.”

In short, while some people might think that analysing all your options before selecting the one with the highest value is the best approach, Simon suggested this wasn’t rational.

“You’ve got time pressures to consider – especially in a chess game,” says Campitelli.

“So Simon says chess players set a threshold in which they would be satisfied. If one of the options reaches that threshold, that’s the option they go with, rather than analysing all the possible options. You look for the one that’s satisfactory, not optimal.”

Sometimes it’s good to remind yourself that near enough is good enough in order to move on with more high-value work.

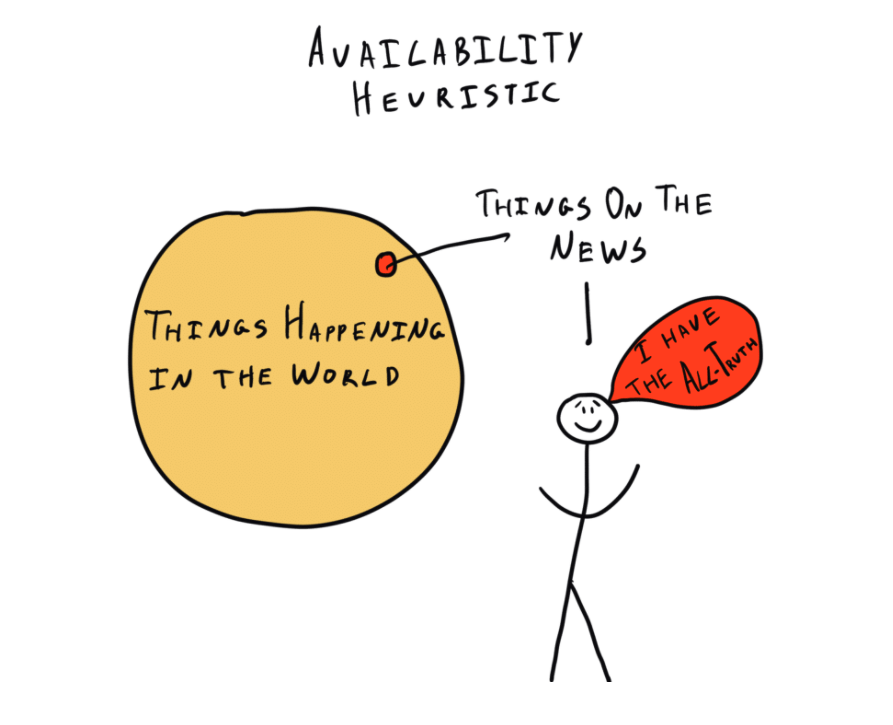

“Availability heuristics help us to judge how frequently things occur without needing to go through our [mental] filing cabinet of evidence. – Ryan Metcalfe, cognitive scientist and lecturer at University of Queensland

Ideate options alone

Renowned Wharton Business School professor Adam Grant is a proponent of individualising the decision-making process. We shouldn’t be making decisions as a group, he suggests. Instead, we should formulate options on our own and then take that to the group for feedback where we finesse and tweak the idea.

Groups are far more efficient at building on an idea – that’s when diversity of thought makes all the difference – but you’ll just get stuck in circles if you’re trying to make decisions as a pack, or you can fall intro groupthink or authority bias, says Ryan Metcalfe, cognitive scientist and lecturer at University of Queensland.

“People in the group tend to go in a specific direction and then, through social conformity, everyone follows along. Everyone feels convinced that they’re all making a really good decision, but there’s no diversity,” says Metcalfe.

He refers to an experiment in which participants had to guess the amount of jelly beans in a jar.

“You can have 100 people make an estimate of how many jellybeans are in the jar, and if you take the average of those estimates, pretty much every time it will be the single best guess out of all of the 100 people.

“However, if you give people the opportunity to speak to each other before they make their estimate, they will anchor on each other’s guesses and you reduce the diversity in those estimates, so your average is worse.”

Understand how heuristics help and hinder

Without even realising, our brains develop mental shortcuts, known as heuristics, that help us bypass the process of trawling through our memory to gather the information we need to make a decision.

“Heuristics are intuitive judgments where we don’t necessarily need to think very hard,” says Metcalfe. “By relying on these shortcuts, we’re able to take those little decisions throughout our day and increase our efficiency without [relying heavily on our] mental processes.”

In many cases, this is a great thing. It means our cognitive load isn’t depleted following the many micro-decisions we face each day – What coffee should I order? Should I take a left or right turn? Should I hit the snooze button again?

However, there are certain decisions that require considered thought, says Campitelli. In these instances, heuristics can do more harm than good. This is especially true in a workplace sense.

Take an employee who is exhibiting bad behaviour, for instance. Metcalfe says a manager might call on ‘the availability heuristic’ when addressing the matter.

“The availability heuristic helps us to judge how frequently things occur without needing to go through our [mental] filing cabinet of evidence. We use the ease with which we can recall instances of a particular thing to make a judgement about how often it happens,” says Metcalfe.

For example, say an employee has been performing poorly since they returned to the workplace after lockdown, but they’re generally one of your top performers. They’re late meeting a deadline for the third time this week, and you notice they’ve forgotten to follow up on an important email. If you pull them into a performance meeting, you might be more likely to come down hard on them due to the recency of their performance issues.

You could assume they’ve always been forgetful or conclude that meeting deadlines is a consistent challenge for them. Heuristics can lead to systemic biases, says Metcalfe.

“Things that come to mind easily are salient in our memory – they’re things that may be highly emotional or surprising. Perhaps you’ve only seen a couple instances of them, but they’re easy to remember, so you might make an unfair judgement.”

So how do you pull yourself out of this? Be systematic in your decision-making, he says.

Relying on gut feelings alone is unlikely to generate the best result. Use those gut feelings as an indicator that you need to dig a little deeper and investigate and bring in a third party to consider whether bias is coming into your decision.

Be conscious of your existing cognitive load

If you have too many options, you become overwhelmed, says Campitelli. It’s called the Paradox of Choice or decision fatigue.

“You start getting confused when you’re presented with too many options and you start making worse decisions if you consider all the options,” he says.

That’s why people like Mark Zuckerberg talk about wearing the same style of t-shirt every day. It’s one less decision they need to make. This might make you roll your eyes. Is anyone really that busy that they can’t choose a shirt to wear that day?

“I’m not so sure about the claims about picking a different coloured shirt is going to fatigue my capacity to redesign Facebook,” says Metcalfe.

It’s less about reducing the number of decisions you make and more so about reducing the type of decisions you’re making, he says.

“Cognitive load refers to the amount of mental strain that we’re dealing with at any given time while we’re trying to complete another task.

“If I’m drafting a report and then I get an email from my boss reprimanding me, that’s quite stressful. I also know that after work, I’ve got to go to my couples counselling session with my wife and I’ve got a deadline in the next half hour. I’ve got a lot on my mind… in that case, I’m probably not functioning optimally as I’m burdening my executive functioning.”

When faced with big, complex decisions that need to be made, Metcalfe suggests taking time to pause and reflect on the various factors that are potentially competing for your cognitive resources. If there’s too much going on, the old adage ‘sleep on it’ can do wonders.

Final quick decision-making tips

-

- Implement bayesian reasoning – Campitelli says this is about not getting stuck in your prior beliefs while also not throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Amalgamate your existing view with new information to “update your beliefs”.

“It happens a lot in organisations where they’re looking for a new way of working, for example, and they think they need to abandon the old approach. The knowledge that you’ve acquired so far should be incorporated with new ideas.” - Schedule things into your diary, such as when you’ll go to the gym or grocery shopping. This means you don’t have to carry around that mental load in your mind all day, says Metcalfe.

- Don’t let expectations cloud your decision-making process, says Metcalfe.

“If you feel like your boss is a grumpy person, any situation you go into with [your boss] will be coloured by that expectation,” he says. “The interactions we have with people are inherently ambiguous; every single thing that we perceive is an interpretation.”

Because this happens automatically and unconsciously, it can be hard to avoid. He suggests considering your situational and environmental factors as a way of bringing some of these biases into your consciousness. “It requires deliberate, mindful practice. Seek feedback from other people before you draw conclusions based on your own interpretations.”

- Implement bayesian reasoning – Campitelli says this is about not getting stuck in your prior beliefs while also not throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Amalgamate your existing view with new information to “update your beliefs”.

Ryan Metcalfe will be unpacking the Sunk Cost Fallacy in the upcoming edition of HRM magazine. Sign up to become an AHRI member to receive your monthly copy.

Insightful article, most interesting. Puts pay to the skills of an exceptional leader (all levels) in particular the leaders ability to (as Adam Grant states above) to set up “individualising the decision-making process’ whilst overcoming ‘groupthink’.