There’s far more to burnout than feeling tired. Burned out employees exhibit a range of symptoms which call for proactive management and sustainable work cultures.

With productivity pressures growing, many global leaders are investing huge amounts of time and resources on cutting-edge tools to enhance their efficiency, from generative AI to virtual and augmented reality.

With that said, for leaders to make the most of the opportunities presented by these new tools, they first need to turn their attention to the wellbeing and efficacy of the employees using them, said Dr John Chan, Managing Director at Infinite Potential, during an address at AHRI’s recent NSW State Conference.

“[As leaders], we can’t do all the great things that we want to do and help people unleash their potential if the environment they’re working in is not healthy or sustainable,” he says.

“Look within – look at the policies, the processes, what you’re doing. If you can improve that, you’ll instantly improve [employees’] activity and quality of life.”

Chan recently co-authored a global report on the state of workplace burnout, which found that almost two in five employees (38 per cent) currently report experiencing burnout – a similar level to last year, and a 27 per cent increase since 2020.

Significantly, the report also uncovered a gap between how managers perceive their people’s wellbeing and how employees themselves reported on their wellbeing.

The report, which surveyed over 2000 participants across 43 countries, found that almost seven in 10 managers (68 per cent) say employees’ wellbeing is the same or better compared to 12 months ago. Meanwhile, 45 per cent of employees said their wellbeing is worse in the same period.

“There are two reasons that we’re seeing this,” says Chan. “One is that managers are much more likely to be burned out themselves, so they don’t have time to actually [address it]. The other one is about education and training.

“[Many] managers weren’t trained to look for burnout or stress. They weren’t trained to know how to mitigate these kinds of things. They were promoted because they’re really good at what they do… but they don’t have these abilities.

“If we’re going to put the onus of taking care of people’s wellbeing on managers, we need to make sure they know what to do and have the tools to do that.”

“Look at the way a job is structured or designed, and [ask yourself], ‘Can one person actually do that job within the time allocated? Are they getting paid enough that they can live and not [worry about] the rent?’” – Dr John Chan, Managing Director at Infinite Potential

Three dimensions of burnout

Part of supporting managers to address burnout is helping them understand what it looks like, says Chan. Many see burnout as simply a synonym of ‘feeling tired’, but the condition is a multifaceted one that must be understood in its entirety in order to be managed effectively, he says.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), burnout is “a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed,” and is characterised by three dimensions:

1. Exhaustion

Exhaustion can take a number of forms, including physical, mental and emotional depletion.

Levels of exhaustion often correlate to the volume of an employee’s workload, but can also be exacerbated by factors such as low job control, which can drain employees’ sense of involvement and engagement with their work.

“Exhaustion is the one we all know, and a lot of the time people think burnout stops here,” says Chan. “But if you’re exhausted but love what you’re doing and you’re [achieving] goals, you’re not [necessarily] burned out.”

Rather, burnout is the combination of exhaustion with the other two dimensions, he explains.

2. Cynicism

Employees experiencing burnout often develop a cynical outlook, mentally distancing themselves from their work and their colleagues and approaching tasks with negativity or even callousness.

“When you see people starting to hate their job, hate the people that work with and hate everything about their role…that’s a lot more problematic than the exhaustion piece when we’re trying to fix the situation,” says Chan.

“Once someone grows that cynicism, it’s a really difficult road [to come back from].”

3. Reduced professional efficacy

This dimension of burnout could involve increases in mistakes and feelings of incompetence, which are often not grounded in truth, says Chan.

“You might be very capable, but because of burnout, and because of the pressures that you’ve been put under or the culture you’re under, you’re starting to make mistakes and you’re starting to doubt your capabilities,” he says.

Given that employees experiencing this symptom tend to take longer to complete tasks, it can create a vicious cycle of playing catch-up and lead to a “burnout spiral”, he adds.

Enjoying this article? Help HRM create useful resources to enhance your HR practice by completing our reader survey. Share your thoughts for the chance to win one of five $100 shopping vouchers.

Combating burnout through sustainable work practices

Managing the dimensions of burnout explained above requires transparency and open communication from leaders to ensure employees don’t begin to self-blame, which only exacerbates the issue, says Chan.

“Burnout is not the fault of the individual. It’s not something that they have or haven’t done that has called them to burnout. It’s not that they aren’t good at prioritising. It is chronic workplace stress, and so it’s the structure and culture within the organisation that’s creating this environment.”

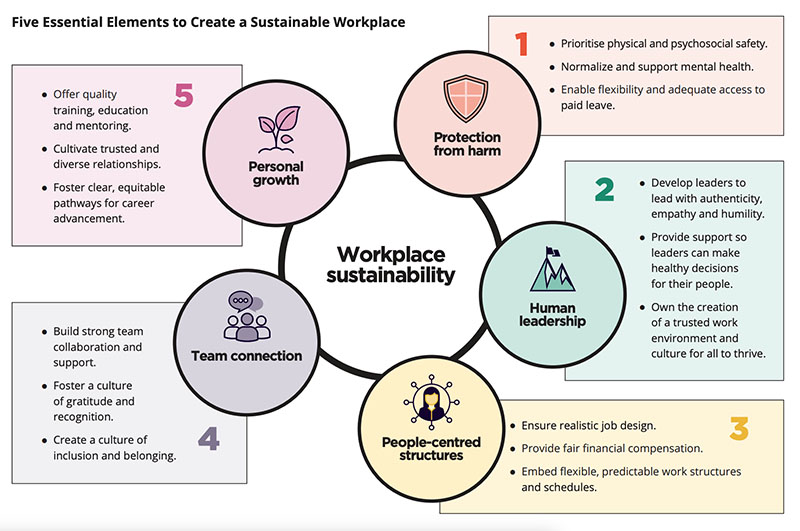

Based on Infinite Potential’s research, Chan’s team has devised a five-part framework for creating a sustainable workplace – i.e., a workplace where burnout is less likely to occur.

The five foundations of a sustainable workplace include personal growth through training and career development, protection from harm and strong connections among teams.

See the full framework below:

One of the most important aspects of this sustainable workplace model is people-centred structures, says Chan.

“This has so much to do with an employee’s wellbeing. Look at the way a job is structured or designed, and [ask yourself], ‘Can one person actually do that job within the time allocated? Are they getting paid enough that they can live and not [worry about] the rent?’ [Thinking about] all of these structural things will do much more for wellbeing than other initiatives,” he says.

While providing career development opportunities to employees whose workloads we are trying to reduce might seem counterintuitive, Chan stresses that these opportunities are essential to give employees a sense of purpose and thus mitigate burnout.

“They still want to grow. They want to do less work, but to keep growing professionally and as a person. So don’t think that if we want to improve people’s wellbeing, it’s all about just taking stuff away from them,” he says.

Instead, it’s about providing opportunities for meaningful work and reducing the volume of stress-inducing tasks.

To effectively apply this structure, Chan says employers need to be willing to trial and test sustainable work strategies that work for them.

“No one knows the right answer. There is not going to be one right way [to approach] the future of work. It’s going to be different within organisations and within teams, and it’s going to change. So be open to experimentation.

“If you’re engaging with people on how you should try something, and [telling them], ‘This is an experiment and it might not go well,’ people really buy into that. So don’t be afraid to try it.”

Learn to design a wellbeing strategy tailored to your organisation’s unique needs with AHRI’s Implementing Wellbeing Initiatives short course.