We’ve lost the ability to look across the room and see if our colleagues are doing okay, so it’s important employees are equipped with self-care tools to check in with themselves.

“I’m doing fine.”

Context usually determines how we interpret this sentence. If the person saying it is avoiding eye contact, speaking softer than usual or welling up, you can quickly determine they aren’t fine. If they’re chipper and smiling, you would be less inclined to investigate further. But when someone types the sentence out, you’ve got little choice but to take their word for it.

A problem with a virtual office is you never really know how someone’s doing. You don’t know if someone has been quiet all day. You can’t see if they have puffy eyes from crying. You can’t tell if they skipped a meal break.

In this time, our workplace support networks look and feel quite different – each individual is carrying much more of their mental health load themselves.

This is why it’s critical HR professionals educate employees and their managers about self-care. And no, not bubble-bath-glass-of-wine-face-mask self-care, but the kind of self-care that empowers people to nurture healthy habits and coping mechanisms.

The history of self-care

The term ‘self-care’ has interesting origins. According to an article on Local Love, it was coined by medical practitioners working with institutionalised patients. In an effort to help vulnerable people (elderly/mentally unwell) and those living with long-term illnesses, medical professionals would provide them with tools to care for themselves in order to give them a greater sense of autonomy over their health.

In the 60s, academics started looking into the psychological impacts of emotionally draining types of work – such as therapy, medicine and emergency services. In this time, the concept of self-care started to focus more on prevention. This is captured by the procedure taught on airplanes today – you put your own oxygen mask on first before you help others.

In the US, The Women’s Liberation Movement and the Civil Rights movement politicised self-care.

“Women and people of colour viewed controlling their health as a corrective to the failures of a white, patriarchal medical system to properly tend to their needs,” writes journalist Aisha Harris in an article for Slate.

“Activists saw that poverty was correlated with poor health, and they argued that in order to dismantle hierarchies based upon race, gender, class, and sexual orientation, those groups must be able to live healthy lives. In turn, living healthily ‘required the involvement of individuals and communities in their own health promotion.’”

The rise of wellness as a lifestyle brand in the 80s, 90s and 00s (think Jane Fonda workouts, yoga retreats and kale smoothies) has made ‘self-care’ a $10 billion industry that, at its most ludicrous, encourages people to pay $123 for a “rose quartz crystal-infused water bottle” from Goop. (No, this is not a joke.)

So self-care has gone from being a medical term, to a deeply radical act, to a capitalist enterprise and frivolous hashtag on social media. Mental health professionals and advocates want us to evolve it once again, and start seeing it for what it should be: a set of personal strategies that help us live a well-balanced life.

“It’s about enabling people the time to build [good] habits into their everyday routines and personal careers,” says Marian Spencer, head of operations people and culture at mental health research organisation Black Dog Institute.

She says self-care also about taking the time to identify specific challenges and trigger points, and creating a plan for how to manage them.

Will self-care become a critical business skill?

In the weeks following Trump’s 2016 presidential victory, Google searches for ‘self-care’ in America spiked. This year, the trend in US searches for the term tracks with the peaks and troughs of COVID-19. But self-care shouldn’t just be something we reach for in a crisis, it should be part of our everyday lives.

“Whether self-care is people seeking some planning around their own resilience on an individual level or more of an organisation wide initiative, what’s essential for workplaces is that managers [and HR] create a culture in which self-care is accepted and encouraged,” says Spencer.

Unfortunately, self-care isn’t something we’re great at in Australia, says Rhonda Brighton-Hall FCPHR, founder and CEO of Mwah (making work absolutely human).

“We’re a long way behind countries who take mental health in their stride,” she says.

Brighton-Hall worked in the Netherlands in the early 2000s. She remembers a colleague saying that she wasn’t feeling well mentally, so she was going to take a few days offs to go hiking in the forest.

“I responded in a way that conveyed ‘your secret is safe with me’, because in Australia at the time you would never tell people you’re not doing well and so need to go bushwalking. But as she was leaving early, she yelled out to the office, “Bye everyone, see you on Monday!” And people yelled back at her, “Go well. Call if we can help with anything.

“We just wouldn’t do that in Australia. We might tell a close colleague or a boss, but we wouldn’t announce it to the whole company,” she says.

While this might be the way of Australian workplaces pre-COVID-19, there has been a shift in the way we talk about our mental wellbeing over the last few months.

In the early days of lockdown we were bonded over a shared struggle and saw leaders being more transparent about their personal challenges. Whether or not that changes as we return to work is yet to be seen, but a recent report from KPMG predicts that leaders who don’t forefront employee mental health will see worse outcomes.

“A few years ago, companies started bringing in wellbeing experts to talk to you about a wellbeing topic, diets for example. That’s become quite a flippant version of wellbeing,” says Brighton-Hall.

“The tools we tend to give people are phone numbers to call and places to visit when they’re not feeling okay, but we also need to have a more open conversation so people can understand their own wellbeing and understand that it’s not static.”

Spencer says there’s a business case for investing in mental health and self-care strategies. Mentally healthy staff produce better quality work, while less healthy staff tend to increase an organisation’s presenteeism and absenteeism rates.

The language of micro-care and self-care

Spencer says organisations should think of mental health and wellness in three tiers: organisational, team and individual.

Mangers, leaders and HR professionals all play a crucial role in the first two tiers. And there’s a trickle down effect between the tiers; individuals will not be set up to succeed unless those first two tiers are in place.

Looking at the organisational tier, an important step is removing any stigma attached to conversations about mental health. To do that you need mental health literacy in the workplace, says Spencer.

At a team level, leaders should be encouraged to engage in acts of micro-care. Managers should be touching on mental health in the conversations they’re having with their teams.

“It can be couched in general social chit-chat,” says Spencer. “You might start the day by asking people if they’ve been for a run or a walk, or ask what they plan to do for lunch that day. The main thing HR leaders and managers need to do is come from a place of real, authentic leadership.”

Brighton-Hall says, “It’s about connectivity and having tiny conversations that gradually develop the language around self-care and give people permission to join a mental health conversation with confidence.”

The language organisations use can have an enormous impact.

“A word I think is important during COVID times is ‘intimacy’. As soon as you start using words like this, it makes people think about if they’re participating in that,” says Brighton-Hall.

“You don’t want people to think, ‘I’m the only person in my team who has a young child with me’ or ‘I’m the only person with a tiny house with not so great furniture’. The individual who feels that way puts a Hawaiian background behind them. But when leadership uses words like intimacy… you’re inviting them to join the conversation in a thoughtful way.”

A self-care template

So what does the individual tier look like? Getting others to adopt self-care behaviours might feel challenging, but you can begin the journey with something as simple as a self-care plan each employee formulates for themselves.

But before jumping into planning mode, Black Dog Institute suggests people consider the ‘reflect, examine and replace’ method. This involves laying the groundwork to make sure each person’s plan is as effective as it can be. It could be something that managers and their teams do together, if everyone involved is comfortable.

Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Reflect: look at your existing coping strategies and behaviours and analyse what does and doesn’t work.

- Examine: identify your main barriers to self-care and work out (individually or as a team) how to overcome them.

- Replace: if you’ve identified any previous negative coping strategies, try and replace them with something positive.

The next step is for individuals to identify their areas of concern, says Spencer.

“That might be that they’re drinking a lot, they’re not sleeping well or they’re getting cross at their family. These indicators would mean it’s time to look at your self-care plan because it’s not good for you and it’s not good for the organisation.”

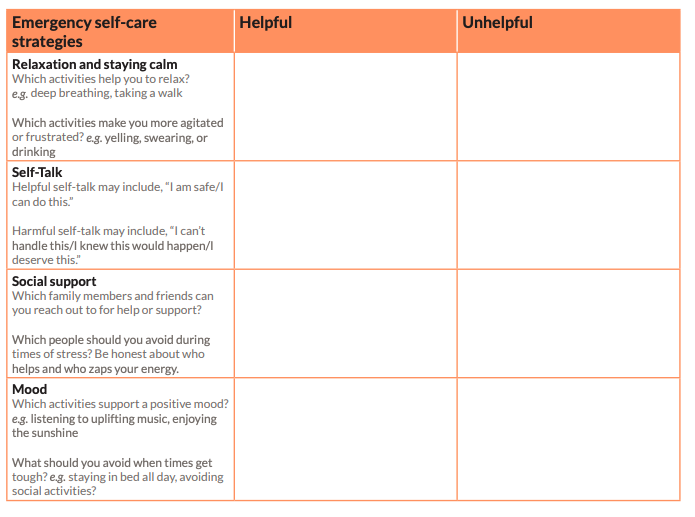

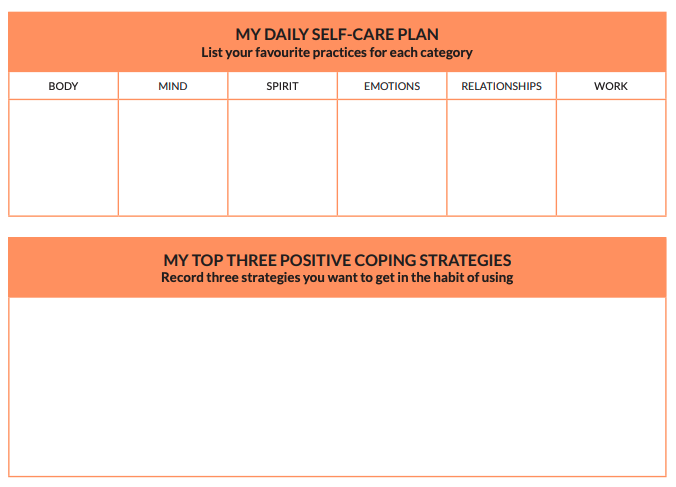

Once they have done that, they can outline what self-care looks like for them. Black Dog Institute has people separate this into two categories.

The first is daily needs, which encapsulates physical, emotional, spiritual, professional, social, financial and psychological needs, as well as emergency self-care strategies.

The second includes information about who makes up an individual’s support network, strategies for positive self-talk, activities that lift an individual’s mood or the trigger points for someone’s stress/anxiety.

Once this information has been determined, it’s time to put the plan in place. Black Dog Institute has developed a great template for workplaces to download, but Spencer also encourages people to use whatever works best for them. You can also refer to HRM’s previous article on developing a ‘personal situation plan‘ if you’d like to customise your own template.

People might like to have their self-care plan pinned to a pin board or desktop, or saved on their phone, so they can refer to it when needed, says Spencer.

“I haven’t looked at mine for ages, but knowing where it is has planted the seed in my brain.”

Learn how to lead an engaged and mentally strong workforce with AHRI’s upcoming webinar, Stay engaged, energised and well. Wellbeing Lab co-founder Danielle Jackson will take participants through professor Martin Seligman’s ‘PERMAH wellbeing framework’ and more.

This webinar is free for AHRI members.

The clincher

Effective role modeling from leaders is one of the most powerful drivers in ensuring people actually follow their own self-care plans. Leaders can wax poetic about the importance of wellbeing all they want, but if it’s clear to their teams that their leader is not practicing self-care, they won’t either.

For example, if people can see their manager is working through lunch, they will feel compelled to do likewise – they will see it as an implicit expectation. This pattern holds true for all sorts of behaviours.

“When senior people send an email at three pm on a Sunday, I just go straight back to them and say ‘Use the email scheduling function,’” says Spencer. “ If you’re going to work like that and not look after yourself, at least look like you are… it’s critical leaders lead by example.”

One of the small things Black Dog does to encourage better behaviours is highlight when senior staff are taking annual leave.

“We’ll say so-and-so is taking leave this week because it’s the school holidays and he thinks it will be a good opportunity to spend some time with his family. These things seem really simple, but they’re communication strategies that contribute to a culture where self-care is accepted and encouraged.”

“Role modelling is about genuinely being part of the conversation,” says Brighton-Hall. “Not just talking the talk or handing a cheque over to a mental health organisation. It’s about saying, ‘I’ve had a really tough time this week. I’m feeling lonely and a bit sick of my own company, how’s everyone else feeling?’ And while staff might not open up and share their feelings in that meeting, they know they can come to you in the future because you’ve said that it’s okay.”

While self-care plans can be very helpful, it’s important to remember that they won’t work for everyone.

“Some people have a very strong wall around them,” says Brighton-Hall. “They might feel like having their friends and family support them is enough. Other people are very comfortable with telling people about what’s going on.”

We’re all trying our hardest to make sure COVID-19 has silver linings. We’ve done what we can to re-think work and restructure our organisations. Many of us have adapted to company-wide remote work, and learned to juggle the challenges of working from home. And some people have even managed to develop valuable new skills.

But we have to make sure that each and every person feels comfortable enough to say, ‘This has been an extremely challenging time in my life and I’ve not been coping well’.

“We love the idea of growth through lessons and pain,” says Brighton-Hall. “But there’s a point where that environment is so bad for you, that you actually denature. You go hard trying to cope but eventually you just stop being you.”

This is exactly why we need to empower everyone to manage their own wellbeing. If we’re going to be spending more time working from home, we all need to be champions of our own mental health.

If you, or someone you know, is struggling right now, you can visit the Black Dog Institute website for helpful resources. If you require more immediate support, you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

[…] fallen to the wayside for many of us. With our interactions reduced to virtual connectivity, it’s harder for us not only to look out for our colleagues but also ourselves. The lines are blurred between work and leisure now that we are working from […]