To mark AHRI’s 80th anniversary, HRM looks back on how the HR profession has evolved over the past 80 years of work.

As we contemplate the role of the modern HR professional, a rich tapestry of terms such as ‘strategic business partner’ and ‘executive influencer’ come to mind. But HR wasn’t always seen this way.

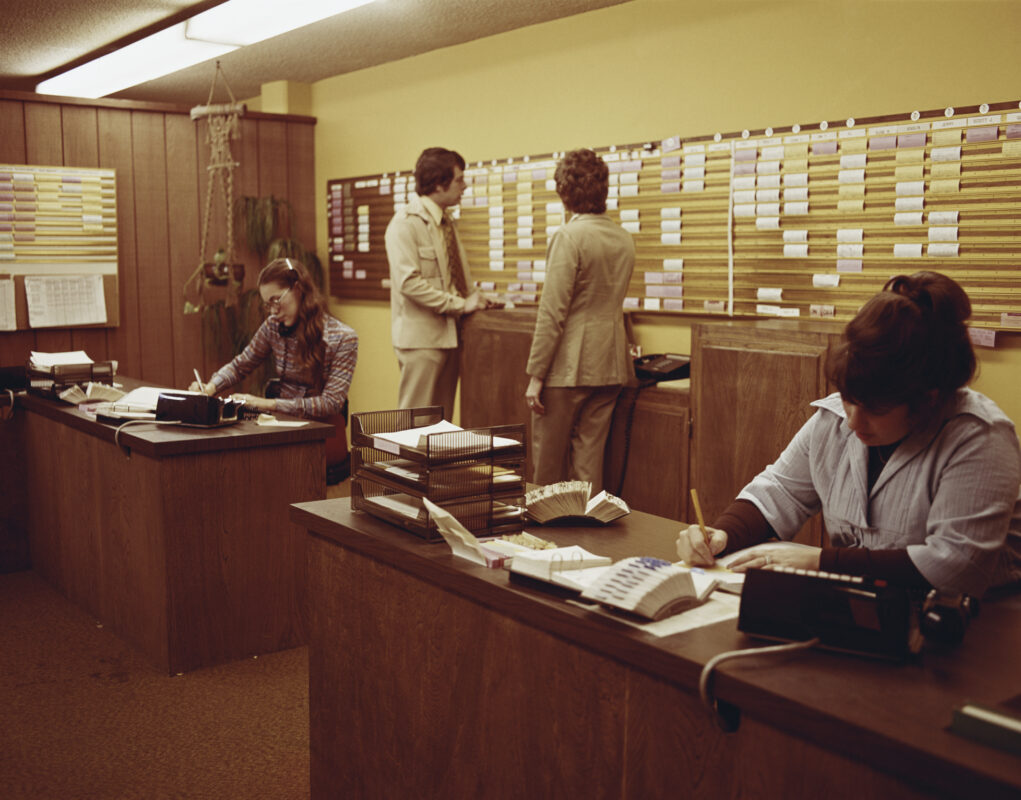

For years it battled to redefine its role beyond an administrative function confined to the back office. This is because work used to be transactional. Employees came and went, dutifully punching their time cards, and most employers didn’t put much thought into how to motivate or reward them beyond sending out their paycheck on time. But as the decades rolled on, HR evolved.

“I think there have been three dominant phases for HR, and we’re coming up to a fourth,” says Peter Wilson AM FCPHR Life, former AHRI Chair (2006-2020).

“In the first wave [1940s-1960s], the context for HR was command-and-control leadership. Personnel were the bureaucrats and policemen of workplace rules. The theory was that you listened to the alpha dog [the CEO] and did what you were told.

“The second stage [in the late 70s early 80s] was about learning how to get the workforce to be more adaptive – there were lots of courses on innovation and entrepreneurship for HR, but we didn’t quite move all the way out of that ‘workplace policeman’ bubble.”

The third wave occurred in the late 1990s to early 2000s when HR started to become influenced by the thinking of behavioural scientists and positive psychologists, he says. Employers started thinking more holistically about employee wellbeing and motivation.

The fourth phase, which HR is currently navigating, calls for a diverse skill set that spans the financial, technological and strategic sides of a business. But before we talk more about what an effective HR leader looks like in 2023, let’s look back at some of the moments that got us here.

1940s-1950s – Personnel comes on the scene

If the Industrial Revolution is credited with the rise of machinery, then it was the 1940s that elevated the significance of skilled labour.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 created a new job market in Australia, focused on the mass production of war-related goods such as ammunition. However, with over a million Australians serving overseas, there was a significant shortage of workers. As women around the world entered traditionally male-dominated fields such as engineering and manufacturing for the first time, the employment landscape shifted.

Australia’s job industry boomed with the introduction of female workers, which helped factories resume mass production.

However, as soldiers returned home, it became clear that the post-war recovery efforts would be significant. Australia lost 34,000 lives during the war, and many of those who survived were not mentally or physically fit to return to the workplace.

It was a time of extreme labour shortages and high turnover.

“[Employers] had to start thinking, ‘What are we going to do besides just giving people a job and paying them? What kind of incentives can we provide to retain staff?’” says Dr Justine Ferrer, Senior Lecturer in HRM in the Department of Management at Deakin Business School.

This period marked the emergence of HR, or an early version of it. While there were industrial and labour relations roles pre-1940, it wasn’t until the post-war period that the concept of personnel management emerged in the Australian context.

“Recruitment challenges, turnover and incentivisation were really influential [in the 1940s]. It was argued at the time that these were a passing trend and things would soon go back to ‘the way things were’, but they never did. It just kept evolving.

“There are so many parallels we can draw with work and HR today – change management challenges, a push for efficiency, and pay alone no longer cutting it as a motivating factor for employees. It’s all cyclical,” says Ferrer.

1960s-1970s – Women at work

Before and during the 1960s, work was fairly rigid, according to Meryl Stanton PSM, FAHRI, former AHRI Board member, organisational psychologist and Chief Executive of Australian Public Service agencies Comcare and the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Agency.

“When I first started work in the late ‘60s as a sales assistant in a department store, I had a bundy clock where I’d clock on and clock off.

“In the public service, you signed on at 8:30am, and if you weren’t there by 8:35am, your pay would be docked. And you’d finish at 4:51pm because, factoring in lunch, that got you 36 and three quarter hours for the week,” says Stanton, who is also a Fellow of the Institute of Public Administration, Australian Institute of Company Directors, and Centre for Strategy and Governance

“That’s so different to the flexibility that many employees enjoy today.”

The impact of the women’s movement in the 1970s can’t be overstated, she adds. By 1974-75, the equal employment opportunity movement was in full swing.

It was, as Stanton puts it, a period where the “basic hygiene factors” of equality were starting to be taken care of.

“Even though the equal pay legislation was passed in 1969, it wasn’t fully in place until 1971, so my first few pay packets weren’t the same as my male colleagues’ pay packets.”

It would be quite a few years until larger changes were made to further support and elevate working women.

“I had my son in 1978 and had quite a unique role at the time – I was the Public Service Board’s Chief Psychologist. I said I wanted to take 12 months’ leave [only three of which would be paid] and they said, ‘Well, you can’t keep the job.’ Flex-time wasn’t an option at my level.

“I even asked if it would be possible to come back at a lower level, but that wasn’t possible either. These were the rules, even in the Commonwealth Public Service’s central HR agency.”

Recruitment was also very different in the ‘70s, she says.

“It was the era of mass selection testing. Jobs were simply offered in order of merit. There were no interviews, generally speaking. In the public service, there was one selection test for people who had matriculated and a separate test for those who hadn’t.”

Towards the end of the decade, and as part of recommendations from the Royal Commission into Australian Government Administration in 1974-76, there was more devolution and public sector agencies had more say in who they hired. At this stage, job interviews became more common.

“Another thing that started changing at this time was the thinking that you could bring in people at the middle level, and sometimes at the top level, from outside the organisation.

“This was a bit of a revelation for the banks and public sector. You didn’t have to come in at the bottom anymore. That made a huge difference,” says Stanton.

1980s-1990s – Technology speeds work up

The 1980s was a huge time of change in the world of work. Globalisation brought new technologies to our shores; the casualisation of the workforce began; and Australia’s union movement continued gaining traction.

“From the ‘80s to the ‘90s, it was the evolution of personnel to HR in a more proactive function,” says Peter Holland, Professor of HRM at Swinburne University.

It was the time of the dot-com boom, which saw companies ‘fighting’ for the best knowledge workers to join their ranks and drive businesses in new and exciting directions. This meant that attraction and retention strategies became more complex and strategic as employers clambered over each other to be considered an ‘employer of choice’.

Professor Timothy Bartram, Professor of HR Analytics at RMIT University, says this was a point in time when many Asian economies started to rise.

“Particularly in South Korea and Japan, there was a rise in economic domination in terms of total quality management, and the [mass] approach to manufacturing goods and services,” says Bartram. “They were masterful at taking American concepts and adapting them to their unique and rich cultures.

They developed new ways to think about productivity and engagement of the workforce, and that really sparked the Harvard model of HRM in 1984-85.”

Dr Gerry Treuren, Senior Lecturer at the University of South Australia, says organisations started moving towards business-unit HR functions in the 1980s.

“The seminal HR texts from the mid-1980s called for the decentralisation of HR. These texts argued, sensibly, that HR people needed to have local knowledge to be effective and assist line managers to make better decisions on the core HR issues of recruitment, training, performance management, etc.”

“[This was followed by] interest in linking HR activity to better meet organisational needs in operational terms, and a more strategic focus where HR was seen as a tool to orient latent capacity within the workforce towards the organisation’s goals.”

Emotionally intelligent leaders

In Wilson’s opinion, the 1990s was one of the most significant time periods of change for HR, as the function finally began to shake loose the idea that they were simply the hire-and-fire bureaucrats. This is what he refers to as the third wave of HR.

“We started thinking more about strategy and assessing the best options. That led to a big shift in western thinking about HR, which, I think, was [characterised] by the workings of Daniel Goleman on emotional intelligence,” he says.

“I also think neuroscientists and positive psychologists taught us that good leadership is about understanding how people think and react, and that the way to lead them is to understand their expectations and needs to get them to want to contribute. Not telling them what to do.”

2000s-2010s – GFC years and the war for talent

The mid-2000s were dominated by the mining boom and global financial crisis. The GFC saw businesses strip back practices, budgets and resources, and learn how to operate in a lean manner.

“Anecdotally, employers wanted to keep their workforce, presumably after struggling to fill vacancies during the labour and skill shortage prompted by the 2004-07 mining boom,” says Treuren. “After the GFC, there seemed to be a few quiet years, but that disguised a silent redundancy round and skills shortage as organisations reorganised business units.”

This was also a period that saw a “once-in-a-generation” change in employment regulation, says Treuren.

“This legislation had several big effects. First, it added a new level of technicality to the HR practice. Secondly, the longstanding IR/HR divide broke down, with HR people being more actively engaged in IR issues.

During the GFC recovery years, when workplaces were once again faced with skills shortages, employers realised they needed to rethink engagement strategies, says Wilson.

“Platforms like Glassdoor were introduced and employees started sharing their experiences of working for companies and, as a result, staff started voting with their feet.

“A crisis, whether it’s a war, a depression, major job losses, strikes or a pandemic, is often a turning point for the economy and how the workplace functions,” says Wilson.

That workplace shift in the early noughties was an integral aspect of moving HR into a more strategic function.

The 2022 State of HR report, co-authored by Ferrer, Treuren, Holland and Bartram, shows that 75 per cent of the people interviewed said there was an HR voice sitting at the C-suite in their organisation and 64.4 per cent reported their organisation having a strategic HR agenda.

“Dave Ulrich, in 1996, talked about HR’s roles as a ‘strategic partner’ and ‘change agent,’” says Treuren. “While organisations had been slowly devolving HR functions to business units, the first I heard the term ‘business partner’ as a job title and the focus of HR discussion around 2010, with senior practitioners.”

“We need to shift towards a more neo-pluralist approach whereby there’s more emphasis on mutual gains between employers and employees.” – Professor Timothy Bartram, Professor, HR Analytics, RMIT

The rise of certified HR professionals

HR’s expanded portfolio and strategic focus started surfacing conversations about giving the function ‘a seat at the table’.

Of course, when you consider HR’s contributions today, it’s clear the function has moved well beyond this narrative. But, at the time, conversations about the ‘next step’ for HR were common; people wanted to lift the function out of the weeds of work.

AHRI played a huge role in shifting this narrative when it launched the AHRI Practising Certification program in 2016 after two years of groundwork.

“We were essentially telling our members, ‘We want to enhance your career,’” says Wilson. “The top professions in the world have self-regulation of their professional accreditations. HR was a standout because it didn’t have strong standards that other top professions had.”

The sentiment from people was that this was the natural next step for the HR profession, says Stanton.

“If it was expected that your CFO would be certified, why wouldn’t your CHRO be?”

2020s and beyond

Holland says the State of HR report found there was once a perception that HR was “sidelined” as the function between personnel and management to “grease the wheels”.

“But during this [latest] survey, there was an increasing [perception] that HR was extremely important. The pandemic has brought us 10-15 years ahead into the future,” he says.

The report found that HR professionals deem leadership, change management and strategic workforce planning as top skills to develop over the following five years in order to evolve their roles.

With these skills honed, Treuren expects HR will play an increased role in organisations as we move into a new world of extreme events.

“[That could include] climate change, big changes in work processes and skill requirements, the arrival of generative AI, increasing threats of cyber-hacking, and increasingly virtual and geographically-dispersed workplaces.”

Now it’s time for HR to maintain their hard-fought influence, says Bartram.

“We need to shift towards a more neo-pluralist approach whereby there’s more emphasis on mutual gains between employers and employees. Employees should share in the stake of the business,” he says.

HR can be slightly circumspect when they get a seat at the table, says Bartram, due to the way they’ve been trained.

“They’ve typically shied away from data. The ability to collect, analyse and interpret data is critical to making strategic business decisions. There are plenty of people who are comfortable managing data, but by and large it’s a growing education opportunity for HR.”

Wilson wants to see HR elevated to leadership.

“We eventually want to see a pedigree of CEOs with CVs [including] experience in HR. If we see that, then you could say the profession has progressed in the same way engineering and accounting has. That’s what I hope to see.”

Where do you hope to see the future of the HR profession? Let us know in the comment section.

A longer version of this article first appeared in the August 2023 edition of HRM Magazine. This article is not an extensive look back on the history of work, but rather a brief recounting of some of the key moments for the HR profession.

an interesting journey, well told, and with some recollections of great distance for some. On latter point, a pedigree of CEO’s with HR experience, I recall in 1990 or so that was a fundamental premise for the company I worked for then (Shell Australia), and indeed Russell Caplan was given a “development” assignment as Head of Personnel and IR, and eventually then became CEO and Chair of Shell Australia – so some were onto it a while back, but still is a core requirement for today in my view, as is HR practitioners having front line, and business operations managerial… Read more »